The different challenges of authentication

Those engaging in professional work addressing cases of art fraud will be confronted to different types of unauthenticity and need to avoid confusion between two distinctive operations:

- The fake object purports to be what it is not, and is characterised by the confusion it creates over authenticity or authorship.

- The forgery, which is a term technically restricted to fake written documents, which can support a cultural object’s alleged provenance.

Fakes themselves can also be divided into different processes such as misattributed work of art, the copy (legitimate reproduction), a pastiche (new object made in the manner of an artist), etc.

Although the production and sale of unauthentic cultural property is generally illegal, faking an object does not necessarily amount to a fraud, which is determined according to the following factors:

- A form of deception by the defendant (usually the seller of the object)

- A victim harmed by the deception

- Dishonesty, intent, and knowledge from the defendant

General overview

Issues of attribution and/or authentication differ among the various fields of art history, from Roman sculptures to pre-Columbian artefacts or painting masterpieces. In each specific domain there may only be a few – sometimes one – experts able to correctly authenticate an object. On the other hand, some categories of cultural goods are the source of conflicting opinions from a wide range of experts. For some contemporary artists, it can be difficult to identify an expert at all, in the absence of academic studies or catalogue raisonné.

The concept of authenticity itself can be confusing when addressing contemporary indigenous artefacts. Such objects can be produced in series, manufactured in the region of origin or elsewhere, and the material is also changing with time. Furthermore, it is harder to detect fake objects, and to identify the “authentic” characteristic of the object. Would it be its age, its place of origin, its maker, the material used, its symbolic or its religious value? In Australia, a label has been produced to protect aboriginal art. The label works as a protected trademark and proved its efficiency, though it would be impossible to duplicate it in other countries.

Authentication can consequently be frustrating for the purchaser of a cultural object, especially without the guidance from a professional who is used to the process and its complexities. The challenge posed by authentication can be discouraging and drive collectors towards unscrupulous acquisitions. Moreover, it is an expensive process, which can be very costly for the victim. In the eyes of the victim, this financial loss might be avoided if the work is not identified as fraudulent, so that it might later be quietly placed back on the market, despite its potential unauthenticity.

Nevertheless, as art has become more valuable, the establishment of authenticity is increasingly recognised as a mandatory prerequisite for insurers, collectors and the art community. This awareness, in conjunction with new technologies, encourages a more in-depth, accurate, and modern authentication process.

Although many art historians continue to issue individual opinions about attribution or authenticity, the greatest caution and legal guidance are recommended when authenticating a cultural object. Art-historical documentation, stylistic knowledge, and technical or scientific analysis, are the three necessary and complementary aspects of best practices for authentication and attribution. These three aspects create a consensus of evidence, which is the best approach to authentication and attribution and the best defense against litigation.

Documentation and provenance

The research for provenance is a vital part in the establishment of authenticity, and the first step purchasers must proceed to. Since the lack of provenance information will increase the risk of acquiring a fake object, the greatest precaution must be taken before deciding to purchase it. Ideally, a complete check for provenance would include all the recommended steps for the conduct of due diligence in order to detect stolen or looted objects.

With regards to the assessment of authenticity therewith, particular attention will be paid to all previous owners' names, dates of ownership, locations kept and means of acquisition, exhibition history and literary citations, progressing in order from the place of origin / production. This includes all kinds of physical evidences: photo-certificates of authenticity, invoices, correspondence, inventory records, gallery and exhibition labels, sale catalogues, collector's stamps, marks and inscriptions, etc.

After acquisition, it is imperative to preserve known provenance, including keeping all documentation in a safe place, and taking precautions during any conservation or framing work to ensure the preservation of all inscriptions, markings and other distinguishing features.

However, provenance research is an arduous endeavor, such extensive documentation is very rare, and never offers a 100% guarantee. As a matter of fact, fake objects often come with fake provenance. Like stolen artefacts, they are often accompanied with forged documents, the quality of which is increasingly impressive. The faking of provenance documentation has become a cutting-edge expertise that can be the central element of organised frauds. If documentation is essential, purchasers of cultural goods can’t rely only on them anymore. For this very reason, provenance research always must be completed with other methods.

The human expertise

When there is an undocumented piece, or when authenticity is disputed, the art market generally rely upon the opinions of third-party authorities such as scholars, museum curators, dealers, auction houses, conservators, the artists, the families of deceased artists and - a phenomenon of the later 20th century - authentication committees.

This common practice places upon us several questions, among those:

- Can the expert be biased towards the object or the owner?

- Is the compensation to the expert above the norm?

- Is the methodology adequate?

- Who owns the most relevant opinion? (in case of disagreements between experts)

In this hazardous context, how can the agents of the market render the process objective? In certain countries, experts are designated by the courts as the holders of the "droit moral" or "moral right" to pass judgment. They are generally members of the artist’s family, sometimes regardless to their expertise. In many cases, these holders of the “moral right” are also recognised as authenticators by the marketplace.

In the absence of catalogue, authentications are dependent on experts’ advices, should they exist. Nevertheless, expert opinion can have less credit than a published catalogue raisonné, notwithstanding the qualification of the expert. “Certificate” expert opinions concerning authentication or attribution are neither infallible nor objective, unless they are supported by a consensus.

In this regard, it is recommended that art historians render opinions only on artworks that are within their competence, and that they be very cautious about issuing such opinions solely on their own authority alone.

Authentication committees

With regards to the fallibility of individual expertise, joint expert opinions from scholars or conservators are usually prescribed, when possible, in order to form a consensus as to the authenticity or attribution of an artwork.

In some countries, authentication committees are established for particular artists. Sometimes these committees belong to foundations who actually legally own the authentication expertise. There can be different types of committees, with different legal forms and purposes:

- Committees selling objects (foundations, etc.), who need to generate incomes and can reject works as unauthentic on the ground that they would compete their collection on the market.

- Committees with no object to sell (scholars and historians), and whose motivation is presumably selfless. They often draft or influence the Catalogue raisonné of the artist.

- Committees formed in response to specific issues (art historians, curators, conservators). They exist as informal groups, which can have huge influence.

(left) J.M.W. Turner’s Agrippina with the Ashes of Germanicus compared with a painting determined by IFAR to be the work of a copyist.

Photos: International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR)

Catalogue raisonné

Catalogues raisonnés are comprehensive scholarly compilations of a single artist’s body of work, usually arranged chronologically, by medium or subject. They are critical tools and prime resource for researching the provenance and attribution of artwork, though their quality and completeness vary widely. They are usually compiled by artists or experts, scholars whose opinion is highly respected. It is very common that the expert is the artist’s relative, descendant, publisher, representative, archivist, researcher, etc.

Notwithstanding their importance, they are fraught with complexities and limitations. Some provide many details (pictures, medium, dimensions, state/editions, condition reports, related works, reference number, provenance, exhibition history, etc.), whereas others offer very scarce information. In both cases, their use requires a professional trained eye.

Moreover, their access remains limited, and they are often only held at limited libraries or art institutions. They also pose the problem of their revision, which can be crucial in case of important discoveries. Finally, as the authorship of a catalogue is frequently a scholar's lifetime project, the compilation can be left unfinished or unrevised at the time of the author's death.

The basic methodology

It is obvious that proper expertise can’t be exercised upon a photograph. There are a number of signs and signals that help determine the authenticity of a piece. Knowing where to look is wining half the battle. Some key basic elements will help starting the examination:

- The style

- The dimensions and proportion

- The materials (type, age, oxidation, etc.)

- The workmanship, construction details and techniques

- The condition

- The signature (media, dimensions, location, mode)

- The inscriptions and marking

- The price

Technical and scientific expertise

It is recommended that art historians rely on specialists employing technologically sophisticated analytical techniques for the material analysis of objects.

Among all the scientific techniques used by experts, the following ones are the most common:

- X-ray

- Fluorescence X

- IR & UV light

- Thermo luminescence

- Colour tests

- Analyse of the materials (pigments, paper, wood, paint, ink, fibre, etc.)

- Mathematical probability

- Dendrochronology tests

- Carbon 14

Chemical analysis of the pigments, photographic or x-ray analysis of the structure, examination of the chemical composition of the canvas or paper, and analysis of the structure of the wood cannot attest the authenticity of an object, but clearly prove its unauthenticity.

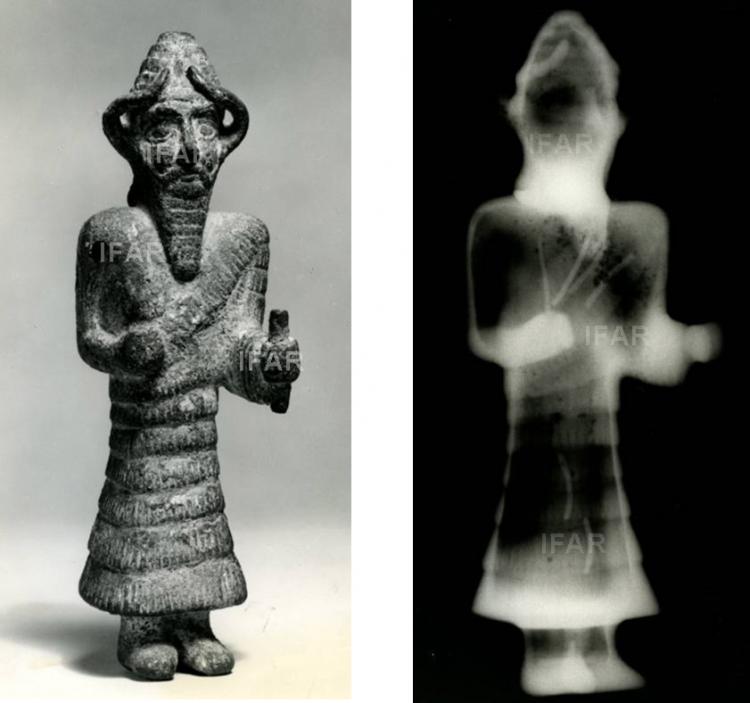

Statuette submitted as an ancient Assyrian bronze, found by IFAR to be a modern fake; (right) x-radiograph showing modern soldering pins.

Photos: International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR)

Microscopic examination of a painting submitted as a purported Jackson Pollock; detail.

Photos: International Foundation for Art Research (IFAR)

The legal issues

Authentication is a matter of opinion, and experts can always be wrong. Therefore they often try to protect as far as possible their judgment from any claim from the parties involved in the transaction of the work or its owner.

In this regard, experts employed by an institution are encouraged to render their opinion with the full knowledge consent and legal protection of their employer. Some institutions have precise procedures in such situations. Furthermore, they will try, to the extent possible, to communicate their judgement privately, upon specific request, against appropriate indemnification and a signed released of all claims.

They will also try to avoid commenting the character or reputation of the seller or owner of an artwork, preferring expressions such as “misattribution” or “not properly attributed to” to “fake” or “forgery”.

Ethical issues

The role of experts in the authentication of artworks or cultural goods also implies a wide range of core ethical issues. Most of them are detailed in the Code of Ethics for Art Historians and Guidelines for the Professional Practice of Art History, issued by the College Art Association (CAA).

The first ethical threat posed by expertise is the conflict of interest. Experts are obviously discouraged to acknowledge the legitimate the authenticity or attribution for an object they know to be a fake, and – of course – to receive indemnification in exchange. In this regard, it is unethical for an art historian to “authenticate” artworks through publicity to form public opinion.

Art historians are actually encouraged not to charge a fee, unless for the confirmation of authentication, or if they are acting as technical experts or within an acknowledged authentication committee.

Finally, it is unethical for a museum to organize or sponsor an exhibition as to which the authenticity or attribution is questioned unless the doubts are clearly indicated or the exhibition is devoted to assist in the determination of attributions.

The outcomes

Authentication procedures can lead to different outcomes. In many cases the work will be recognised as authentic, whether it is signed or presents some contradictory evidence. In fine arts, the work can also be an unknown copy from the artist of one of its previous work.

In the most complicated cases, authentication methods fail and no consensus can be reached. The information provided by provenance research can be too scarce or not reliable enough, technical analyses can lead to unsatisfactory results, or the experts can’t reach a consensus. In this case, contradictory judgements on authenticity have serious consequences as final legal decisions are taken on the ground of experts’ advices. Determining the authenticity of a cultural good requires a satisfactory consensus of evidence, which is the result of the combination of the three methods. Should art historians disagree regarding the object’s authenticity, the court can hardly render a decision strictly based on documentation or technical analyses.

Should the work be declared as unauthentic, consequences go to a simple cancelation of the acquisition to a prosecution in case of fraudulent intent. Notwithstanding the implication of an acquisition of unauthentic objects by a collector or a museum, there are several degrees of authenticity for a cultural artefact. Fake can of course be built from the ground, they can be copies, but they can also be also be converted objects (assembling of two different parts of furniture); or even objects that went through minor or major restoration processes.